Five Terms You Need to Know about Cell Therapies for Cancer

Researchers are gaining ground on better understanding the interactions between immune effector cells and tumors. As a result, they are finding new ways to boost the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells. Promising treatment strategies that stimulate durable, immune-mediated tumor regression are now being used clinically. If you are new to Immuno-Oncology, here are the 5 terms you need to know to catch up on what’s going on in this very exciting field.

1. Immunotherapy

Immunotherapies are treatments that stimulate or suppress your body’s own immune system to help fight cancer. The most common approaches stimulate the patient’s immune system to work harder or smarter to attack cancer cells.

2. Adoptive Cell Transfer

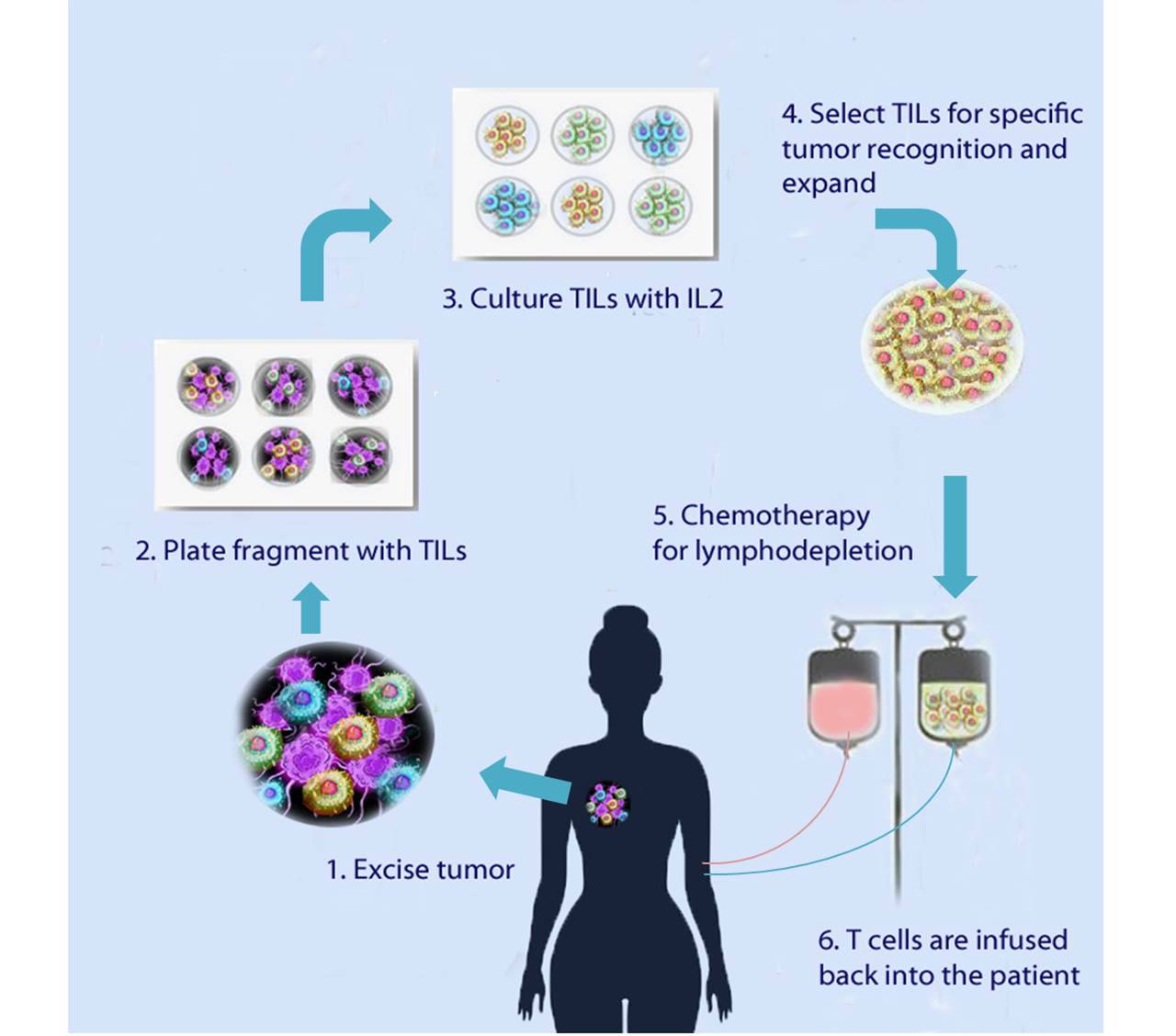

Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) is a very personalized cancer therapy that involves administering immune cells with direct anticancer activity to the cancer-bearing patient. In some instances, complete and durable tumor regression using naturally existing tumor-reactive lymphocytes has been achieved in patients with melanoma and common epithelial cancers. Efforts are being made to apply these advances to other cancer types. The ability to genetically engineer patients’ lymphocytes to express conventional, cancer cell-reactive T cell receptors or chimeric antigen receptors has extended the application of ACT to cancer treatment.

Also, knowledge on the expression of tumor-specific antigens has been accumulating such that tumor antigen peptides may be used to prime antigen presenting cells, such as dendritic cells, to stimulate a patient’s adaptive immune responses before autologous, cancer-killing lymphocytes are reinfused in the patient.

Figure 1. Basic steps in autologous immunotherapy using the patient’s own tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) capable of destroying tumor cells.

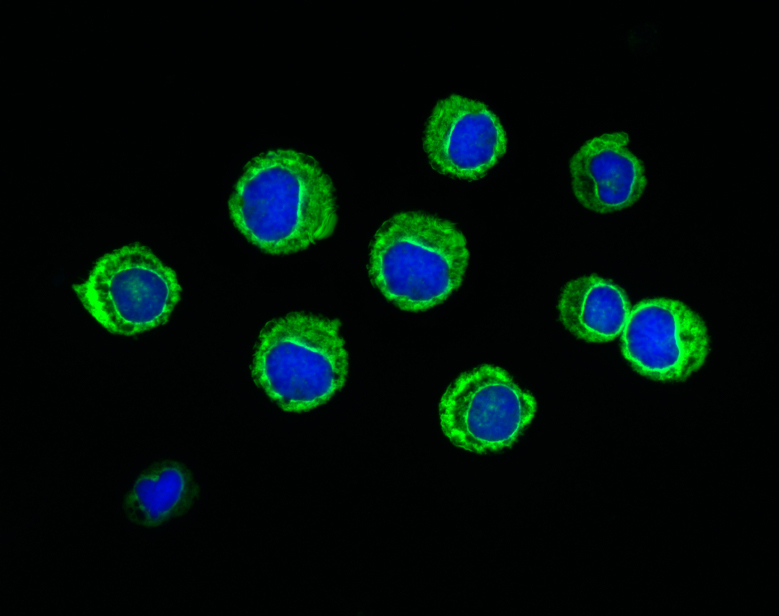

3. Conventional T cell Receptors

These are T cell receptors that are present naturally on host T cells and exhibit antitumor reactivity. Clinicians can collect tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from a cancer patient and grow, expand, and select those that are able to destroy the individual’s unique tumor cells, and then re-infuse them into the patient.

4. Engineered Antigen Receptors

To broaden the reach of ACT to other cancer types, scientists have introduced specific antitumor receptors into normal T cells that can be used for immunotherapy. Like the approach described in the previous paragraph, this technique involves collecting a patient’s lymphocytes and genetically modifying them to express one of two types of receptors:

Antitumor T cell receptors (TCRs)

These are T cell receptors (TCRs) that are genetically engineered to recognize tumor-specific cell surface antigens. Upon re-infusion into the patient, the engineered leukocytes can infiltrate into tumors, and inhibit tumor growth in an antigen-specific manner. TCR therapies require that the tumor cells express on their cell surface the appropriate, processed antigen recognized by the engineered TCR in association with the appropriate HLA molecule, the endogenous antigen-presenting mechanism in all human cells.

Chimeric antigen receptors (CARs)

Another approach consists of using genetically engineered T lymphocytes that express chimeric antigen receptors on their surface that bind to malignant proteins expressed on the surface of a cancer cell. CAR therapies utilize a fusion receptor that couples an antibody-like antigen recognition domain to T cell activation molecules, so that upon binding, the chimeric T cell becomes activated and initiates tumor killing.

T cells engineered to express CARs bind directly to unprocessed, protein antigens that are expressed on the tumor cell surface; they do not require that tumor cells process and present the antigens in the context of HLA protein. CAR-modified T cells have been used extensively to mediate regression of advanced B cell lymphomas, for example.

5. Lymphodepletion

A variety of circulating inhibitory factors are known to repress immune system function and its ability to effectively target and destroy cancer cells. Lymphodepletion -the removal of existing lymphocytes from the patient’s circulation- before ACT, can greatly enhance the ability of transferred lymphocytes to treat established tumors. Typically, pre-treating patients using either nonmyeloablative chemotherapy or a radiation regimen improves the tumor regressing efficacy of reinfused antitumor lymphocytes.

Strategies for using adoptive cell transfer for treating cancer are expanding to include other immune cells, such as primed dendritic cells, monocytes and macrophages. Breakthroughs in new immunologic approaches for treating this disease will depend on the identification of suitable targets for immunologic attack with minimal toxicity. All of these new approaches will require in vivo preclinical evaluation in models such as humanized mice, prior to testing in humans, in order to validate their mechanism of actions, efficacy, and safety.