Are we ready? Genome engineering approved for experiments in viable human embryos

Well, this is interesting. As many people come up to speed on the general implications of genome engineering, researchers are preparing to take the next step.

Scientists at the Francis Crick Institute in the UK are now permitted to use CRISPR to edit the genomes of viable human embryos, at least according to the UK Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). A local ethics board still has to weigh in, but it looks like research using this much-debated experimental platform will commence.

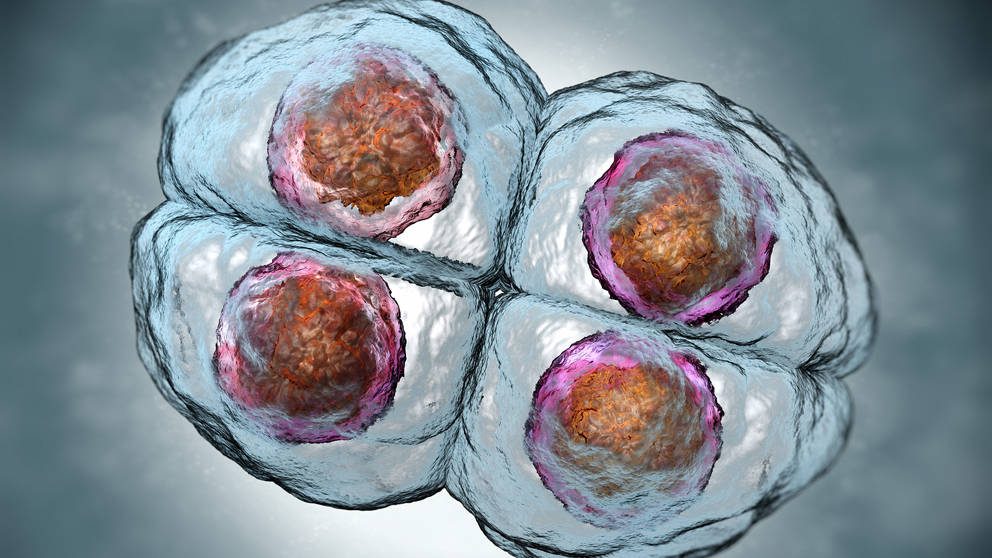

The plan, submitted by researcher Kathy Niakan, is to investigate aspects of the very earliest stages of human development by blocking a gene (OCT4) thought to be an important regulator of the process. The preliminary in vitro experiments will last about a week, halting when the embryos reach the blastocyst stage, comprised of up to 256 cells. No further development or growth will be allowed, and it remains forbidden in the UK to edit the genomes of embryos used to conceive a child. It’s possible that three additional genes will be targeted once the pilot experiment is complete.

As science goes, it’s not that big a deal. The experiment seems well thought out—it has a well-defined scope, and the questions it seeks to address are interesting. Nonetheless, the results are likely to be ambiguous once all the data are analyzed. We’re complicated and genetically diverse organisms, and perturbing a single gene usually has effects that go beyond those expected. Indeed, Craig Venter makes this point in a subsequent commentary, which opines against genome editing to cure disease but is not directly concerned with the experiment proposed.

What is notable, however, is that the approved experiment appears to bring us one step closer to experiments that do edit heritable traits. And as such, I’m surprised that the response has been so subdued. Or, as Tim Caulfied, Canada Research Chair in Health Law and Policy, says in an interesting Q&A on the topic “… it seems like the temperature is a little lower and we are having a quite sophisticated discussion, at various levels, about the benefits and risks of this technology.” Clearly the paper published about nine months ago, in which scientists engineered the genomes of non-viable human embryos, effectively served as the lightning rod in this debate. The outcry at that time was intense, and serious and, yes, sophisticated discussions have been had since.

Those discussions are made even more important by the fact that researchers working on CRISPR/cas9 methodology are not standing idly by while the policymakers and ethicists debate. They have made genome editing more precise and less error-prone, found ways to get the genome editing machinery into cells more easily, assessed other nucleases that might replace cas9 and much more. Furthermore, they have broadened the functionality of RNA-guided genome alteration to include site-specific enhancement and suppression of gene activity, chromosome labeling and more.

The upshot is that what we are able to do with CRISPR has already advanced beyond our thinking regarding what we actually should do with CRISPR. While we’re not to the point of being able to design babies with desirable traits—things like size and intelligence and beauty still defy our genomic understanding—we can make pretty amazing changes to genomes with relative ease, accuracy and efficiency. Make no mistake, this is a huge boon for biomedical research. The quick, precise and inexpensive creation and validation of mice that model human disease has made possible experiments today that took many years or were impossible a short time ago. But once the experimental veers toward the clinical, the benefit and risk equations become far murkier.

So does the Niakan experiment, the first to be sanctioned in viable embryos, conform to the current ethical thinking? It depends on whose thinking you’re talking about and just how slippery the slope is perceived to be.

As we understand more and more about genomics, medical benefits are the promise and the goal. It’s imperative that we continue to push hard for clinical progress. But the questions and serious discussions must persist. In all my time in science, CRISPR is the first technology that brings the great power, great responsibility cliché immediately to mind. It’s truly amazing what we are now able to do. It’s more important than ever to proceed responsibly.

Mark Wanner followed graduate work in microbiology with more than 25 years of experience in book publishing and scientific writing. His work at The Jackson Laboratory focuses on making complex genetic, genomic and technical information accessible to a variety of audiences. Follow Mark on Twitter at @markgenome.

Mark Wanner followed graduate work in microbiology with more than 25 years of experience in book publishing and scientific writing. His work at The Jackson Laboratory focuses on making complex genetic, genomic and technical information accessible to a variety of audiences. Follow Mark on Twitter at @markgenome.