The Consequences of Sex Bias in Preclinical Research Studies

Introduction: The Historical Context of Sex Bias

In 1993, the NIH issued the Revitalization Act which for the first time required the inclusion of women as participants in clinical drug trials. Prior to 1993, many drugs approved by the FDA were tested for efficacy and safety primarily in men, leading to unexpected and potentially dangerous side effects in women. For example, when the sleep aid Zolpidem (commonly known by the brand name Ambien) first went to market in 1992, many women reported impaired alertness after waking up, leading to a spike in car accidents. Eventually it was discovered that there were baseline sex differences in the clearance rates of Ambien that caused the drug to stay active in women’s systems longer than in men’s, and the recommended dosage for women was officially halved in 2013.

The Revitalization Act marked a landmark in improving women’s medicine and health. However, there was no comparable mandate for sex inclusion in preclinical research until 2016, when the NIH announced that all grant proposals must include both males and females in their study design or have a scientific reason for including only one sex. In this article, we’ll look at the historical use of male and female mice in the published literature and consider the importance of including sex as a meaningful biological variable in your research.

Then and Now – a Look at the Publication Record & What it Reveals

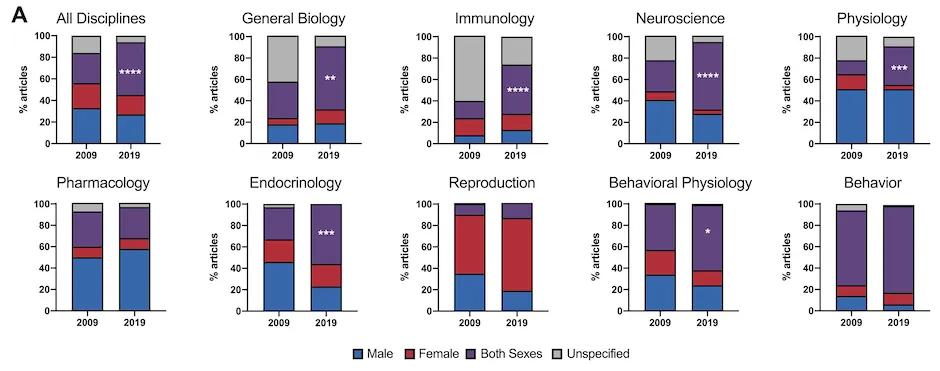

To examine the impact of the 2016 NIH mandate on sex inclusion and reporting, authors Woitowich et al. (2020) conducted a comprehensive review of preclinical research published in 2009 (before the mandate) versus in 2019 (after the mandate). Six of the nine biological disciplines surveyed showed significant increases in the percentage of studies using both males and females. Overall, sex inclusion improved from 28% in 2009 to 49% in 2019, with neuroscience and immunology showing the greatest individual improvements and behavior remaining in the lead with an impressive 81% inclusion (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of surveyed publications reporting inclusion of only males, only females, both sexes, or sex not reported, across nine different biological disciplines. From 2009 to 2019, overall sex inclusion increased from 28% to 49%.

The authors also examined the percentage of publications reporting sex-based analyses and found that this measure decreased from 50% overall in 2009 to 42% in 2019 (Figure 2). While improvements in overall sex inclusion are promising, meaningful analysis of sex as a biological variable is critical for contextualizing results and enhancing reproducibility in biological research. When we default to collapsing data across sex, we risk increasing variability and losing valuable information that could lead to development of novel therapeutics and improve health for men and women.

Figure 2: Of publications that reported including both males and females, the percentage that reported analyses using sex as a biological variable. Overall, this measure decreased from 50% to 42% from 2009 to 2019.

Importance of Sex as a Biological Variable

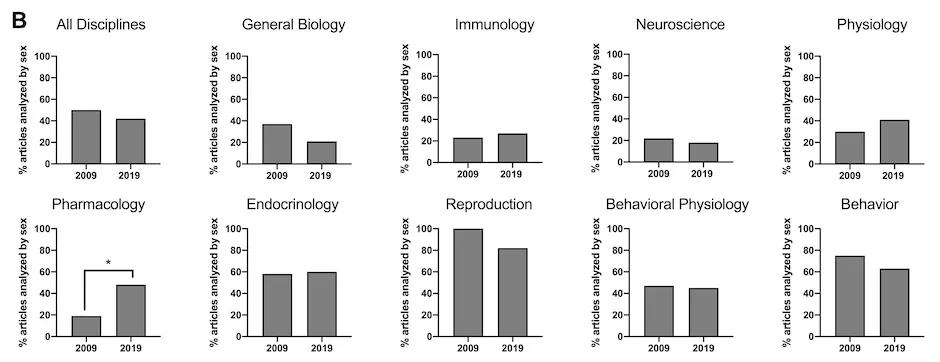

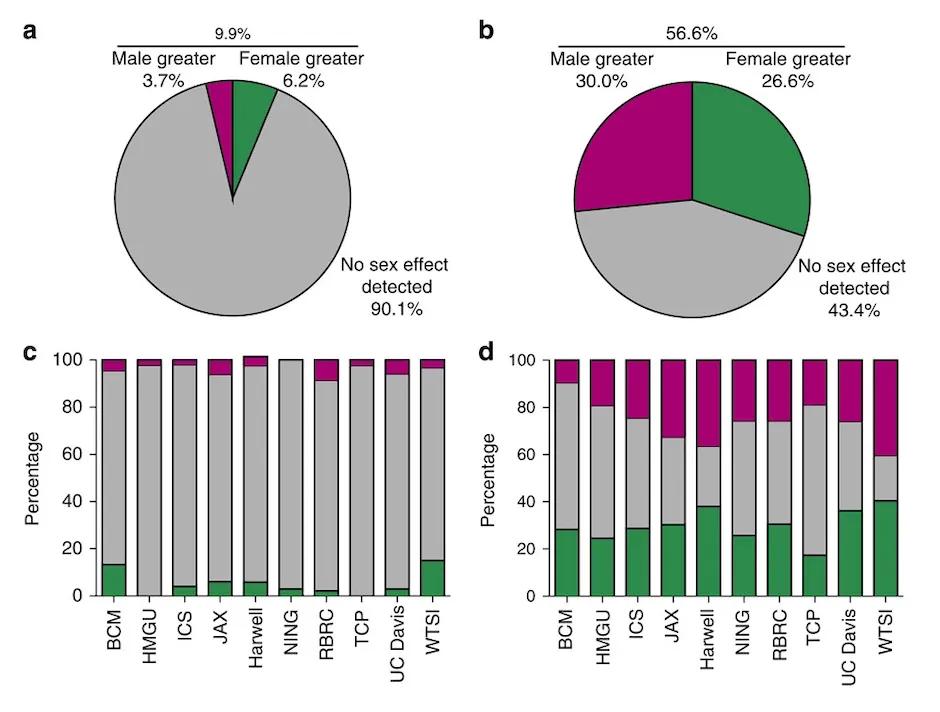

Sex differences are prevalent across biological disciplines. In one collaborative study, researchers from The Jackson Laboratory and 9 other institutions used high-throughput phenotype data from more than 14,000 wildtype and 40,000 mutant mice (including 2,186 knockout lines) to estimate the proportion of phenotypes that show some degree of sexual dimorphism. The datasets included 234 different phenotypic traits overall, quantified either categorically or continuously. For categorical measures, there is little room for nuance and few sex effects were observed. But over 50% of continuously measured phenotypes showed some degree of sexual dimorphism (Karp et al. 2017).

Figure 3: An analysis of 234 different phenotypes across 14,250 wildtype and 40,192 mutant mice housed across 10 different institutions. Less than 10% of categorically measured phenotypes showed any sex effect (a,c). More than half of all continuously measured phenotypes (b,d) showed some degree of sex effect.

There are three primary mechanisms underlying observed sex effects in rodents. Some sex effects are chromosomal, meaning they are determined by genes present on the X or Y chromosomes in males versus females. Other sex effects are influenced by varying levels of sex hormones, like estrogens and androgens. Organizational effects of hormones are exerted during sensitive windows of development, including the perinatal period and adolescence. These effects tend to be long-lasting or even irreversible, such as masculinization or feminization of the brain. Circulating hormones during adulthood can also exert temporary activational effects in males and females. Importantly, hormone levels can fluctuate in both males and females. Despite the common misconception that females are more variable than males, studies have shown that there is no difference in variability of either gene expression or phenotype across sex (Itoh and Arnold 2015; Prendergast et al. 2014).

Looking Forward

While the scientific community has already come a long way towards understanding the importance of sex across biological disciplines, there is still much to learn. By being purposeful about including both males and females in our study designs in a meaningful way, we can bridge the gap that exists between preclinical research and human applications. There is a growing consensus worldwide that studying sex as a biological variable is critical for advancing scientific knowledge and improving human health, and many resources are available today to support researchers in this effort. To learn more, visit the Experimental Design Assistant or Norecopa for additional guidelines.

When considering your own preclinical study design, we invite you to speak with the JAX Preclinical Services team. Our study directors are available to discuss key aspects of your study design such as sex bias and other considerations that ensure your project’s success.

To learn more on this topic, we invite you to view the full presentation “The Consequences of Sex Bias in Preclinical Research”, presented by Dr. Sam Eck, Sr. Technical Information Scientist at The Jackson Laboratory.